Photo: Juliet Lockwood Art.

Jake Kimbrell would like one to focus on everything but the life he has crafted from an early rocky start.

Born in Muncie, Indiana, Kimbrell moved to San Diego at a young age with an older sister who stepped into the breach left by absent parents. When asked about the influence of the loss of parental guidance, Kimbrell briefly stares into space as though uncomfortable before admitting that he became more independent. “I had control of my own destiny,” he explains. “I chose to believe that I could do anything as a result.”

Kimbrell served in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam war era, deployed to Germany. He brushes over that time and draws the conversation to his years at City College in San Diego. He stopped one credit shy of a degree because by that time, he had already started teaching at City College and working in a commercial studio. “The degree seemed superfluous,” he notes.

Commercial work drew him because he could control what the viewer saw in a way that shooting on location didn’t allow. “I created everything you saw,” Kimbrell says, his eyes dancing with the memory. He pursued a successful career in commercial photogrphy for three decades, winning a coveted Addy in 1999.

Kimbrell has always had a yen for helping other artists. In the late 1990s, he started an artists’ gallery in the basement of Back to the Grind, a coffee shop in Riverside. The Gallery, called “Under the Grind”, allowed local artists to show their work in an open venue. He feels now as he did then: Artists need to help each other. A few years later, he rented a tiny office in an otherwise vacant building. He convinced a fellow artist, Glenn Morris, to rent space in the same location. Then he got another idea: Use the other empty offices as a gallery. He returned to the coffee shop and recruited artists, and The People’s Gallery was born. Eighty-five visitors attended the first opening. The Gallery grew from there, swelling in popularity and fame.

Five years later, Kimbrell relinquished management of the People’s Gallery to one of the participating artists. She and others had urged him to start a not-for-profit. He didn’t want to lose control of the creative endeavor, but recognized that a not-for-profit made sense at that stage of the gallery’s development. So he let go; and moved to Minnesota to pursue an artist-in-residence stint at a Minneapolis art co-op.

In an odd way, Kimbrell blames the profound impact of his year in Minnesota for the struggles of the next few years. “After putting all of my effort into helping other artists, I found my own creative energy in Minnesota. I couldn’t go back to focusing only on promoting other artists. I lost myself for a while.” Kimbrell lapses into silence. A question draws him back — why didn’t he return to the commercial art career in which he had found such success? He promptly answers that being a commercial artist satisfied him until he began to think about the impact of his work on those who saw it. It slowly dawned on him that the consumer could be manipulated. He controlled their response. He did not like that feeling.

A lost year followed his return to California. He does not like to dwell on the details, but doesn’t hesitate to credit his children’s mother for saving him. She forced him to get help. Then his daughter and her wife asked him to come north, to the Antioch/Pittsburg area where they lived. Expecting their first child, they wanted to provide a positive male role model for him. Kimbrell did not hesitate. Then, when the two moved further east, to Rio Vista, he came along.

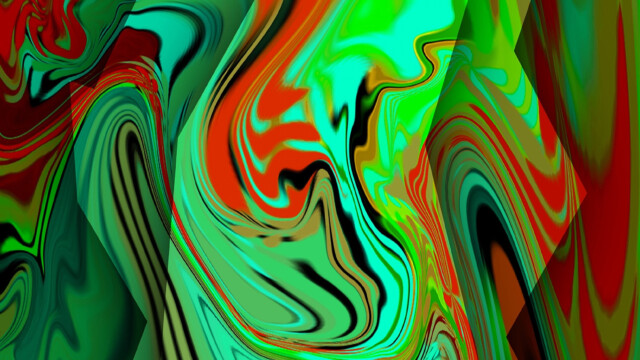

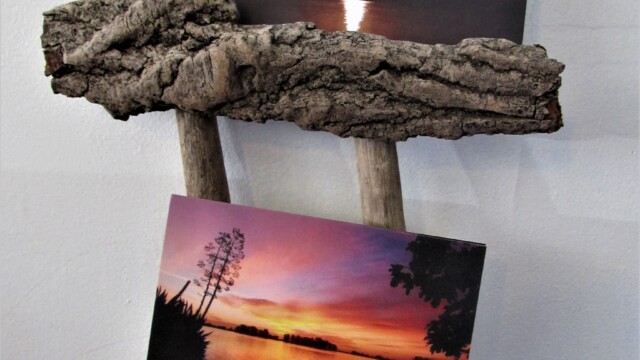

Here, he fell in love with The House by the River, from which he now generates some of the most stunning and amazing photography of his long career; glorious sunrises, heart-breaking sunsets; the sweep and rise of the river and the timeless flutterings of nature. He has also started working with multi-layered digital art, demonstrating the depth of color and complexity which can be coaxed from images by minute manipulation combined with careful control of saturation.

Kimbrell has not abandoned his quest to elevate other artists. He recently conceived and curated a show for artists who are veterans, hosted by Iselton’s newest gallery, the Wandering Gypsy. He and a fellow artist, Robbie Murphree-Gabriel, spearheaded the gathering of creatives which will take place at Park Delta Bay on July 13. He passionately espouses the coming together of artists in the California Delta to enhance the existing community. At the same time, his own creative energy still surges. He’s working on some new techniques of working with digital abstracts. He looks forward to an August show of this new body of work.

Meanwhile, Kimbrell produces and sells art postcards as “The House by the River”, an identity which allows him to let go without losing control. He doesn’t have to acknowledge that the painstakingly beautiful art comes from him. The House by the River brings us the most amazing glimpses of life in the Delta, but Jake Kimbrell, the creative conduit for an everlasting muse, controls the delivery, while the rest of us hold our collective breath, waiting for the unveiling of each new sunrise.

Editor’s Note: On 13 July 2019, twenty Delta-based artists will participate in a group show at Park Delta Bay in the Community Room and under the big tent. We will be featuring profiles of some of the participating artists, of which the following are two. We hope this introduction will inspire you to come see all of the art on display and to explore the work being shown.